History Articles

Featured Articles

Read our latest stories on the people and scientific innovations making a difference in patients’ lives.

Science & Innovation

In Celebrating 175 Years, Pfizer Challenges Itself to ‘Outdo Yesterday’

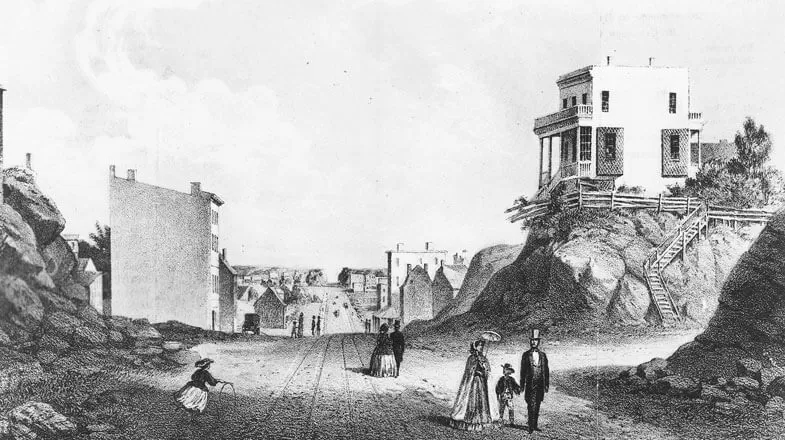

Image caption: Site of the Pfizer World Headquarters Building as it Appeared in 1861It started with a breakthrough.The year was 1849, and people everywhere were getting sick to their stomachs. In the days before widespread refrigeration, a simple meal of meat and potatoes could cause intestinal worms. A drug called santonin could kill the parasites, but it tasted so bitter many people avoided it.Charles Pfizer and his cousin, Charles Erhart, had just immigrated to the U.S. from Germany and...

The ‘Immortalized’ Cells That Sparked an International Incident and Their Role in Producing Medicines

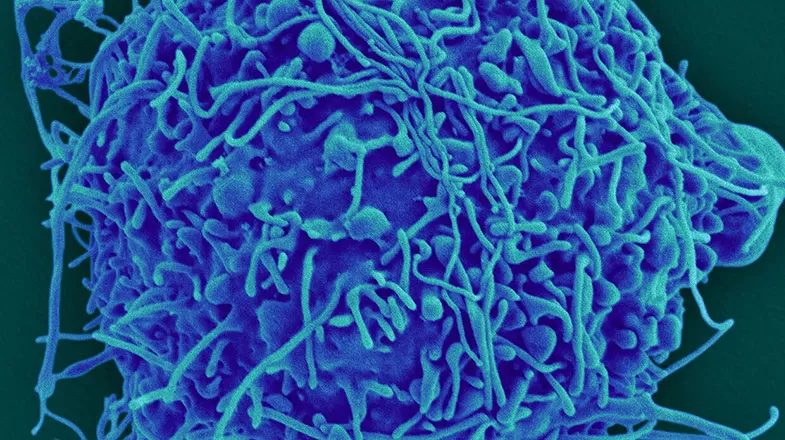

Proteins are the rock stars of biological molecules. They allow cells to carry out crucial functions like growth and differentiation, and enable cells to adapt to changing environments. Because dysfunction in certain proteins can cause disease, manipulating proteins is also the foundation of developing new medicines. But where do we get enough building blocks to actually manufacture the medicines that patients take? It turns out that living cells—which make proteins as part of a day’s work...

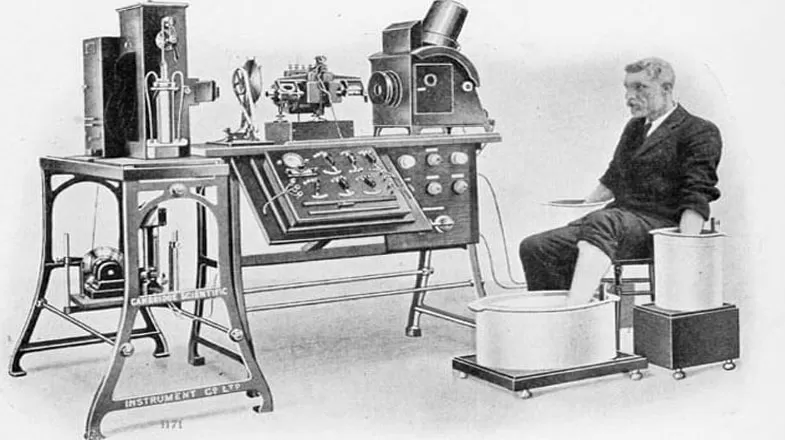

Flashback: The First ECG

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Times} p.p2 {margin: 5.0px 0.0px 5.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Times} p.p3 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Times; min-height: 14.0px} span.s1 {font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'} Willem Einthoven found the beat and built a machine that could measure the electrical current a heart creates. It weighed 600 pounds. An electrocardiogram — called informally an ECG or EKG — measures the small electric waves that a human heart creates. It’s...

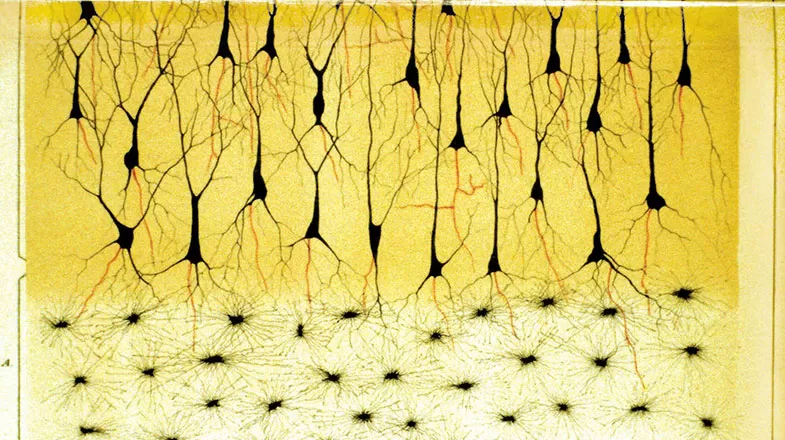

6 Views of a Neuron by Golgi and Cajal

Two groundbreaking scientists stain cells, uncover the intricate secrets of the nervous system, and elevate scientific discovery to fine art. In 1872, Camillo Golgi accepted a job as the chief medical officer at the Hospital for the Chronically Sick at Abbiategrasso, Italy. It is here — ensconced in a tiny kitchen he had converted into a makeshift laboratory — that he created what he would call the “black reaction.” It was a method of staining that was able to capture even the most delicate...

Female Pioneers: Meet the Biochemist Who Tackled One of TB’s Great Mysteries

Florence Seibert was an early pioneer in applying physical chemistry techniques to biomedical problems. American Florence Seibert developed a reliable test for TB, which has helped saved millions of lives. In the early 1900s, tuberculosis, a bacteria that settles in the lungs and eats them away, continued to be among the deadliest diseases, killing one in seven people in the U.S. and Europe. Before the turn of the century, German scientist Robert Koch had discovered tuberculin, which is...

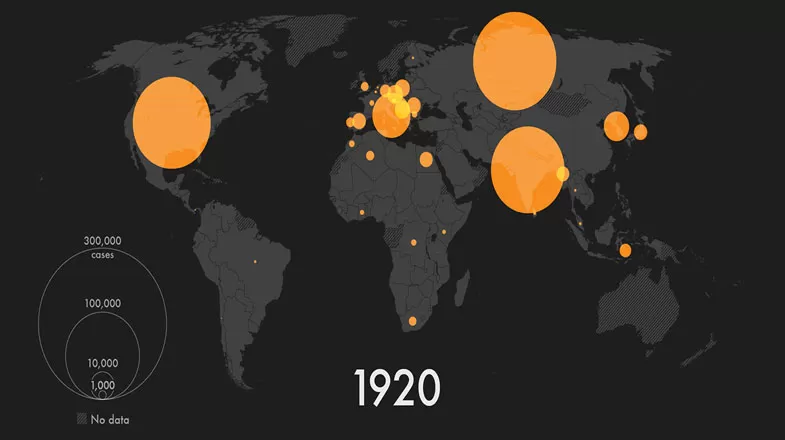

Smallpox Vanquished

Once one of the world’s deadliest diseases, smallpox’s complete eradication was the result of a worldwide deployment of a vaccine begun 50 years ago. To date it’s still the only human disease ever to disappear from Earth. Considered one of the greatest achievements of the 20th century, alongside the likes of getting a man on the moon, and one of the greatest medical feats in all of human history, smallpox was officially declared eradicated from the planet in 1980. The big push for its...

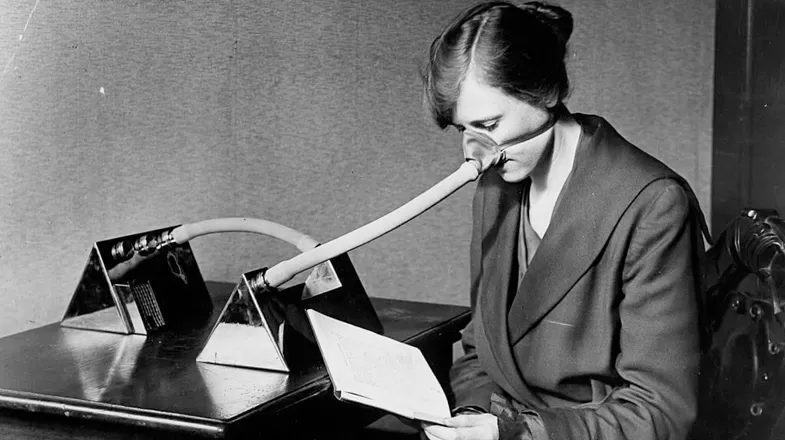

Flashback: Spanish Flu Mask

(Topical Press Agency/Stringer) At the close of WWI, an estimated 50 million people died from the Spanish flu. Masks were the uninfected’s main line of defense. Patient zero of the Spanish flu may have been a soldier in WWI, who accidentally carried his virus back into the densely packed military encampment in Fort Riley, Kansas. From there, the infected would have marched across the battlefields of Europe and beyond, carrying the disease with them. In the end, Spanish flu infected a full...

Flashback: Iron Lung

A medical miracle made of metal helped polio sufferers to breathe in the 1900s. The tank respirator, or iron lung, reads like a medical curiosity in modern times thanks to vaccines for the polio virus created by Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin in the 1950s and 1960s. But prior to that, for the nearly one in every 200 patients infected with the virus that suffered paralysis, including of the respiratory system, it was the surest way to survive until they could recover and breathe again on their own...

Flashback: Carbolic Acid Sprayer

(Science Photo Library) Joseph Lister revolutionizes the world of surgery with an antiseptic idea. Upon reading Louis Pasteur’s work on putrefaction as a result of germs in 1865, budding Scottish physician Joseph Lister was struck with a eureka moment: He wanted to stop the outrageously high rate of deaths, a full 40 percent in the case of amputations, from infection acquired as a direct result of surgery. By 1867, he’d decided that carbolic acid (or phenol, a derivative of coal tar)...

Media Resources & Contact Information

Anyone may view our press releases, press statements, and press kits. However, to ensure that customers, investors, and others receive the appropriate attention, Pfizer Media Contacts may only respond to calls and emails from professional journalists.