In Celebrating 175 Years, Pfizer Challenges Itself to ‘Outdo Yesterday’

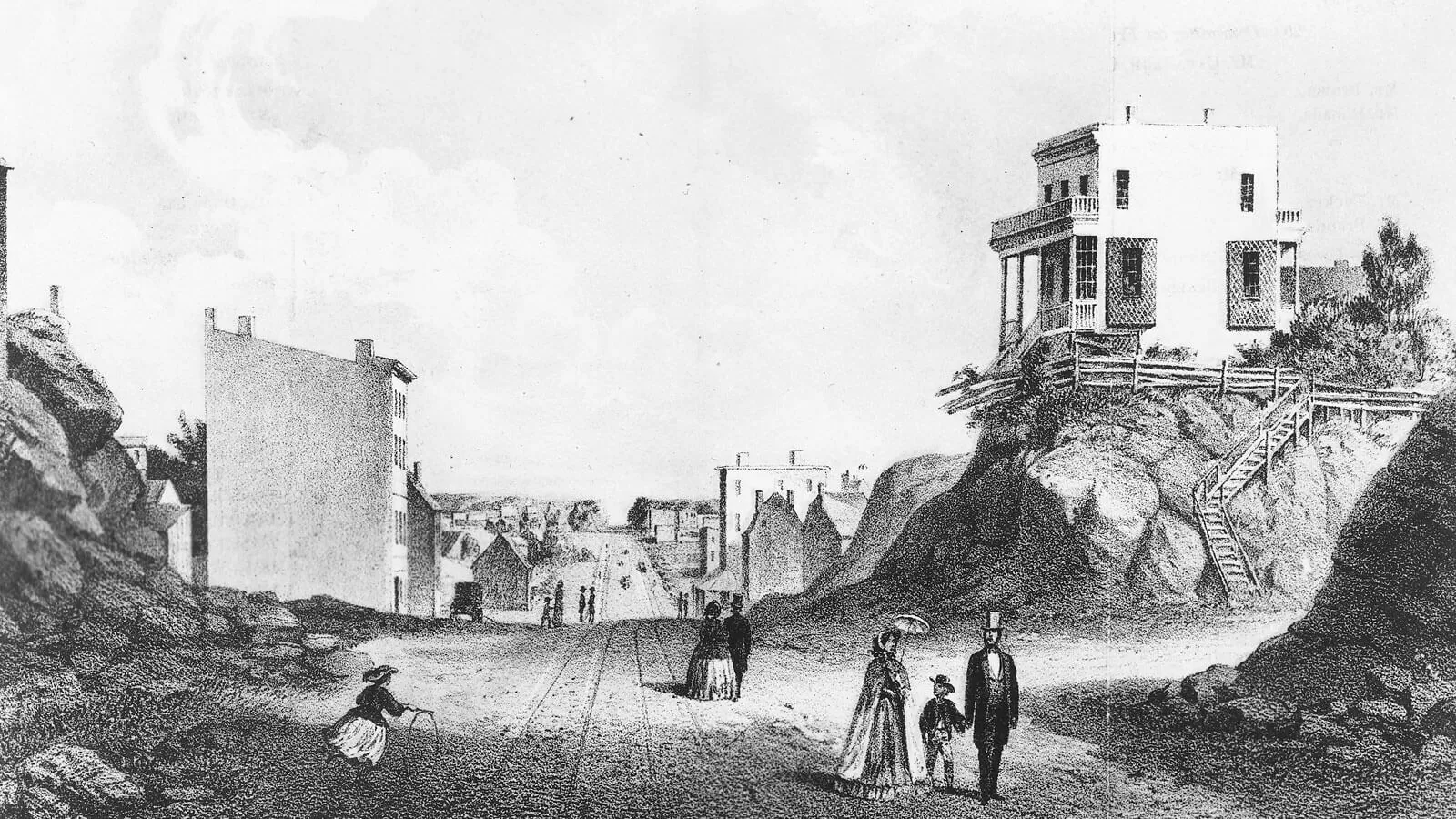

Image caption: Site of the Pfizer World Headquarters Building as it Appeared in 1861

It started with a breakthrough.

The year was 1849, and people everywhere were getting sick to their stomachs. In the days before widespread refrigeration, a simple meal of meat and potatoes could cause intestinal worms. A drug called santonin could kill the parasites, but it tasted so bitter many people avoided it.

Charles Pfizer and his cousin, Charles Erhart, had just immigrated to the U.S. from Germany and launched one of America’s first chemical companies. As they saw people fall ill, they had an idea. What if they were to develop a medicine that tasted almost like candy? Relying on their training in chemistry (Pfizer) and confection (Erhart), they blended santonin with an almond-toffee flavoring, shaping it into a candy cone. It was palatable, and effective. The first breakthrough by Charles Pfizer & Company took off.

That was 175 years ago. And it was the first of countless innovations in science that would go on to shape history and change lives, thanks to the determination and grit of two cousins from Germany.

An American success story

Growing up in Ludwigsburg, Germany, Charles Pfizer learned chemistry as an apothecary apprentice and Charles Erhart learned about the grocery and confectionary trade. They were fascinated by the opportunity and growth they heard about in America, and in 1848, at age 25 (Pfizer) and 28 (Erhart), they took the biggest gamble of their lives: a six-week voyage across the Atlantic to New York. There, they set out to meet the growing demand for chemicals, which were increasingly a necessity in manufacturing, agriculture, and medicine.

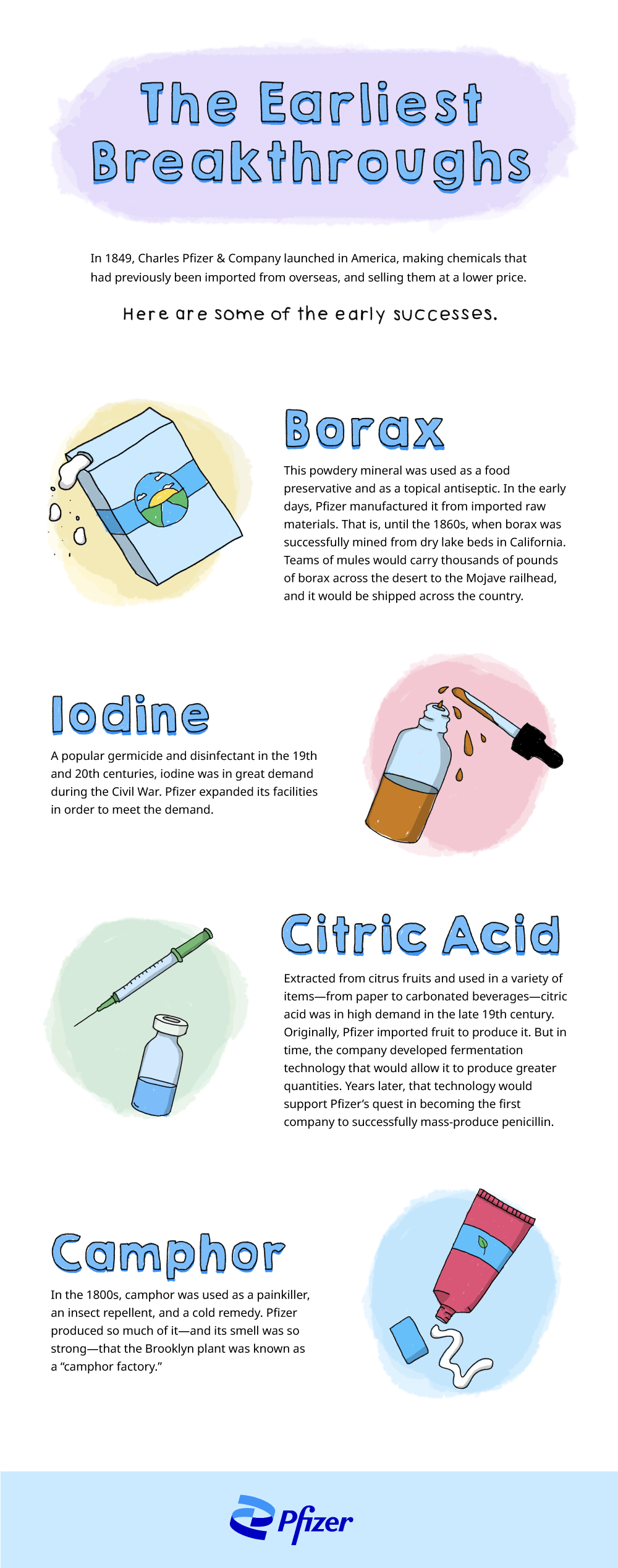

With a $2,500 loan from Pfizer’s father, they bought a humble red brick building in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, to serve as their office, lab, factory, and warehouse. In launching Charles Pfizer & Company in 1849, their goal was to make chemicals in the United States that, at the time, had largely been imported from overseas. Using tariff laws to their benefit, they saw the opportunity to sell their wares at a lower price and gain an instant advantage. Before long, they had a catalog of more than a dozen chemicals for sale, including borax, camphor, and iodine.

When the Civil War began in 1861, afflictions such as dysentery, malaria, typhoid, yellow fever, and venereal diseases were as much a threat as armed troops. Charles Pfizer & Company was at the ready, ramping up production of tartaric acid—a laxative and skin coolant—along with cream of tartar, a diuretic and a cleansing agent, and iodine, which was used as a germicide and disinfectant. Also in high demand were morphine, chloroform, camphor, fungicides, and other chemicals. The growing sales allowed the cousins to buy more land in Brooklyn, as well as in Manhattan.

The years that followed brought recognition and more breakthroughs. In 1876, Charles Pfizer & Company earned international respect when the company was awarded the Centennial Award at the International Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, which drew more than 10 million visitors. Four years later, it unveiled the latest development: citric acid, which was an ingredient in a growing array of products, including papermaking, flavoring food and soft drinks, and dissolving iron oxides; the company quickly became the country’s leading producer of the acid.

In 1899, on Pfizer’s 50th anniversary, Charles Pfizer addressed a crowd at the Drug Trade Club in New York City, offering a peek into the company’s motivation, “Our goal has been and continues to be the same: to find a way to produce the highest-quality products, and to perfect the most efficient way to accomplish this, in order to best serve our customers,” said Pfizer. “This company has built itself on its reputation and its dedication to these standards, and if we are to celebrate another 50 years, we must always be aware that quality is the keystone.”

Outdoing yesterday

Last year, Pfizer’s medicines and vaccines reached more than 1.3 billion people, or one out of every six people on earth. And, while the company’s founders have long departed, Charles Pfizer’s words ring true today, 125 years after they were spoken. Rooted in quality and in service to patients, Pfizer’s breakthroughs continue to support historic moments and events, while preventing, treating, and curing some of the world’s most vexing diseases and conditions.

During World War II, for example, the company responded to an appeal by the United States Government to increase penicillin manufacturing, becoming the largest producer of the “miracle drug” in treating Allied soldiers. Other innovations include game-changing statins that reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke, and an innovative breast cancer therapy that’s been given to more than half a million women and men globally. And, of course, in 2020 Pfizer made history in delivering the first safe and effective mRNA vaccine against COVID-19.

And still, this is just the beginning. Looking ahead to the next 175 years, Pfizer’s motivation, today, isn’t to stay the course—it’s to outdo yesterday. With advances in technology and artificial intelligence, the company has its sights on preventing, treating, and curing many more diseases, including cancer.

After all, anything is possible. Look at what’s grown out of a $2,500 loan and a dream.

![]()