Reducing the Pull of Memories to Fight Drug Addiction Relapse

Researchers are working to prevent drug relapse by reducing the powerful tug of drug-associated memories.

While some may believe that beating addiction is just a matter of willpower, scientific evidence has established that drug addiction is a chronic illness that produces lasting changes to the brain’s chemistry and function. Some 40 to 60 percent of people treated for substance abuse disorders will eventually relapse, according to a study in The Journal of the American Medical Association.

The latest brain research reveals that drug addiction may have such a powerful grip on individuals because it affects our learning and memory processes. “Something as simple as seeing drug paraphernalia or returning to an environment that reminds the user of the drug activates memories that were created when it was first consumed,” says Audrey Wells, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Pfizer’s Internal Medicine Research Unit who is focused on Neuroscience in Kendall Square, Cambridge, Mass. “This can cause feelings of extreme craving to the point where it’s difficult for a person to abstain, oftentimes leading to relapse,” she adds.

How Addiction ‘Highjacks’ the Brain

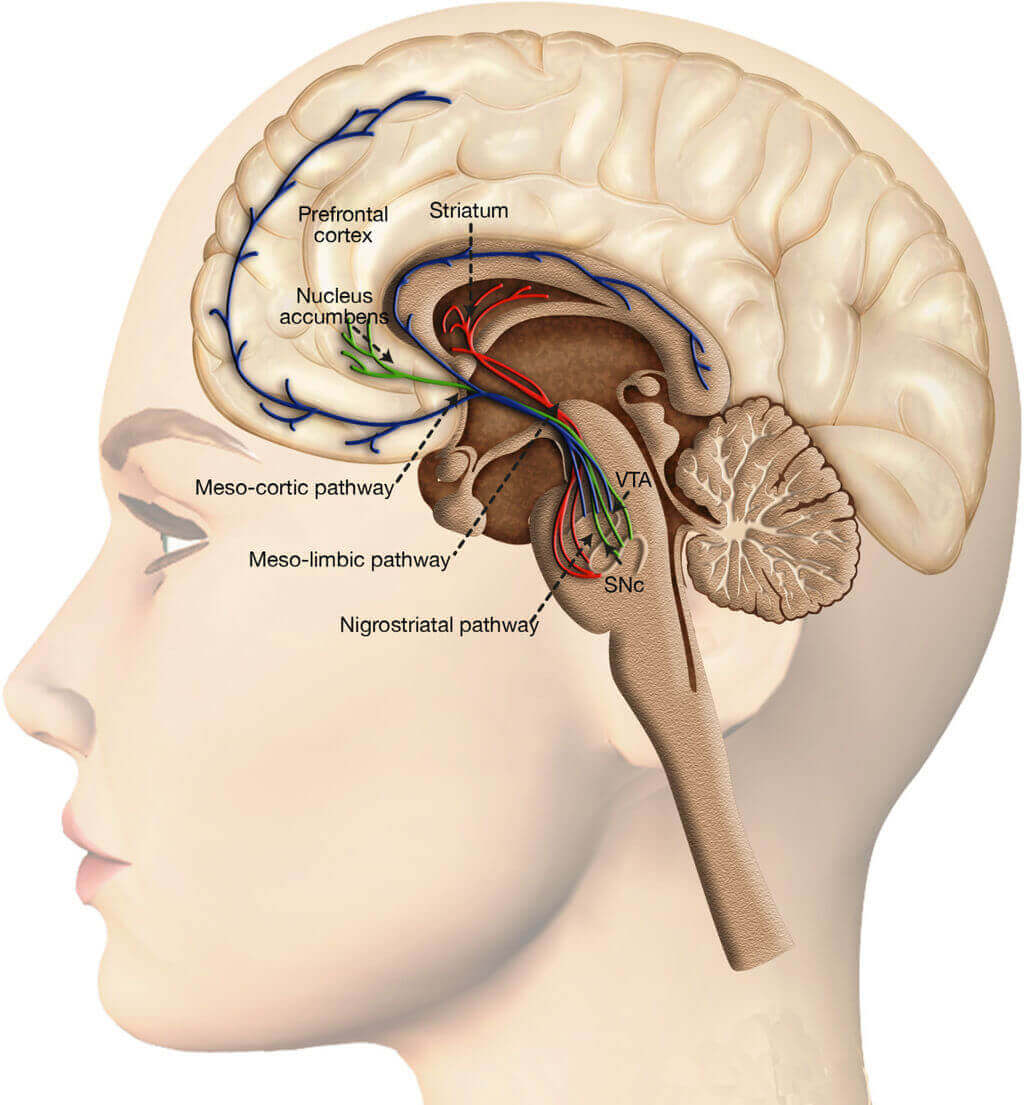

The nucleus accumbens is a region of the brain involved in the processing of rewards that represent our most basic biological needs, such as food, water and sex. When a reward is experienced (for example, drinking water or eating a meal), it triggers the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure, in this region. In this sense, our brains are wired to reward us for repeating these life-sustaining activities.

Most drugs of abuse target the dopamine reward system, which includes the nucleus accumbens and the VTA (ventral tegumental area). Wikicommons/Arias-Carrión et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.2014

Addictive substances have a similar effect on the brain’s reward pathways. When the drug is consumed, the brain learns to associate this activity with pleasure, and to seek it out again and again. These substances are oftentimes more powerful than natural rewards because they release 2 to 10 times the amount of dopamine. “These drugs of abuse hijack the brain’s reward pathways. In doing so, they cause changes in the number and sensitivity of dopamine receptors and the proteins that help carry out the dopamine signal,” says Wells.

A Vicious Cycle

As the brain compensates for the surge of dopamine caused by the drug, a person’s ability to derive pleasure from daily life activities is gradually reduced. “This is why you see things like depression in addicts, because essentially their processing of normal rewards — like going out for a gourmet feast — is blunted.”

At the same time, the brain develops tolerance for the drug, and a person needs to take more of it to achieve the same levels of pleasure. “It’s kind of a vicious cycle,” says Wells. “Once you’ve consumed these drugs it doesn’t take long to produce tolerance, and once you’re caught in this cycle it’s no longer a choice. There are well-documented changes in the brain that cause an individual to seek out these drugs again and again.”

Drugs, Memory and Relapse

When an addictive substance is consumed, a memory of its pleasure is stored in the brain and is strengthened over time as the individual continues to use it. “The brain wants to remember that reward because it’s an important and salient experience at the time,” says Wells.

Even after a person goes through rehabilitation and gets “clean,” these memories remain intact and if triggered by an environmental cue, the desire for the drug can come rushing back. “It’s a major issue,” says Wells. “Without even realizing it they’re flooded with these memories of how the drug felt to them and they can experience an intense craving. Essentially it becomes very, very hard to resist and can drive them to relapse. It’s not really volitional — craving can overpower the desire to remain clean.”

Reducing the Power of Memory

While these memories can never be erased, Wells’ area of research is working on reducing the power and pull of these memories to cause feelings of craving. “My work is part of efforts in both academia and industry to identify chemicals and molecules in the brain that are crucial to the memory retrieval process, so that we can design drugs a person can take so when they return from rehab to reduce craving when re-exposed to these signals,” she says.

Working in animal models, Wells is studying ways to reduce the impact that external stimuli have on triggering memories and craving. “It’s not only about changing the memory, but also changing that motivation that underlies the drive to continue the addictive process. Rather than blocking the effects of the drug, we’re trying to change the way the brain reacts to the possibility of drug consumption.”

One molecule Wells and colleagues are investigating is called casein kinase 1 (CK1), which may help to carry out the effect of dopamine receptor binding in the brain. “We know that dopamine receptor binding takes place when people re-encounter drug-related stimuli , such as locations associated with past drug use. By inhibiting this molecule, we hope to reduce the impact of those stimuli so that they’re less likely to cause relapse,” says Wells.

A Common Myth

For those in recovery, a common myth is that the longer that you’re abstinent the easier it becomes to stay clean and the less likely a relapse will occur. But according to the “incubation of craving phenomenon,” the brain doesn’t return to a normal state right away, and in fact it becomes more sensitive to those drug-associated signals, making you more likely to relapse, according to Wells. The brain activity of people in recovery shows that their reaction to environmental stimuli, such as pictures of drug paraphernalia, continues to increase up until about six months after becoming clean, and even though it plateaus, she says, it still remains high. “Most people think, ‘I’ve been clean for a week, so I must be better.’ You’re getting better but the hump you have to get over may be a lot longer than most people realize and recovery is an ongoing process that requires continued effort.”