Medicine’s 2-Way Dance: What a Drug Does to the Body and What the Body Does to a Drug

We all know that a tremendous amount of brain power, time and resources goes into creating a new medicine. While much attention is given to the “discovery” aspect of translating scientific insights into new therapies, an equally important part of the process involves studying how a potential new medicine will affect the human body and what is the safest and most effective dose.

Caption

These questions are addressed by clinical pharmacologists, scientists who specialize in studying what happens to a drug when it enters the body and how it’s absorbed, metabolized, and eliminated. Clinical Pharmacologists are also responsible for providing important safety information that appears in fine print on a medicine label, such as the maximum daily dose, dosing regimens, potential drug interactions and how the medicine may affect special populations such as children and the elderly.

Gianluca Nucci, Vice President of Early Clinical Development, Clinical Pharmacology at Pfizer, and his team play an important role in designing and conducting phase I clinical trials, the “first-in-human studies” to test a drug’s safety and effectiveness. “Since it’s the first time we’re putting this potential new medicine in people, it’s the moment you have to use all your resources and integrate all the available non-clinical safety and pharmacology data to predict a safe starting dose to do the best job that you can,” says Nucci, who is based in Pfizer’s Cambridge, Massachusetts, research site. “You don’t want to put the subject at risk by dosing too aggressively and you don’t want to waste a huge amount of time testing ineffective doses on the subject, who won’t necessarily benefit from the drug themselves.”

Most phase I studies are done in healthy volunteers. Early trials for oncology treatments, however, usually include cancer patients, because these patients could potentially benefit from them and they might otherwise be cytotoxic, or cell damaging, to healthy volunteers.

Nucci sees this crossing over from pre-clinical to phase I as a pivotal step in the drug discovery and development journey. Scientists are building upon years of non-clinical work, and by studying how the human body handles the drug, they’re helping to paint what he calls an “emerging clinical picture” of where to take the phase II and III studies.

Read on to learn some of the key pharmacological insights gained during Phase I studies.

‘Dipping a Toe in the Water’

The first few people who receive the potential new medicine are often given very small amounts—what’s known as a “sub-therapeutic dose,” meaning it’s only intended to have minimal biological effects and expected to be very safe, but scientists can still measure how it acts in the body. This is a very important moment in the journey of a new medicine and it is highly scrutinized internally as well as by external review boards and regulatory authorities.

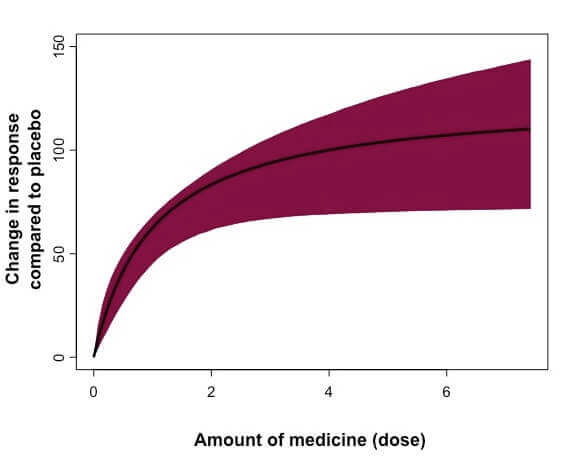

Schematic example of a dose-response curve, which is a visual way to understand data on the effects of varying doses of a potential medicine. The outcome of interest (“response”) may vary depending on the particular questions being asked in that study. (Image courtesy Gianluca Nucci)

The key here, according to Nucci, is to understand the mechanism of action, the nonclinical pharmacology and safety to select an appropriate small starting dose amount, but not so small that the research is slowed for months before reaching the pharmacological dose range. After subjects are given that initial dose, their safety labs, vital signs and ECG are recorded, and they’re kept under observation until the potential medicine clears the body. Doctors keep a close eye on subjects to watch for any side effects. A group of experts are then convened to examine if safety, tolerability and drug levels are as expected and decide whether or not to increase the dose and by how much.

“We continue this process in the same volunteers until we reach the concentration where we’re convinced we’ve properly tested its pharmacology and safety. Dose escalation is carried out in incremental steps. You have to dip the toe in the water before you can swim,” Nucci says.

Two Sides of the Same Pharmacological Coin

The other important aspect of phase I studies are pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD), which are two sides of the same pharmacology coin. PK is what the body does to the drug—how it’s absorbed, broken down and eliminated. PD is what the drug does to the body—examining the onset and offset of the pharmacologic response.

They are both fundamental to drive the optimal balance between therapeutic benefits and side effects and are the basis for getting the dose right.

And every patient is different. For example, the rate at which a medicine is metabolized can vary greatly across people. People may also have pre-existing conditions that may require adjustment of the dose. Or they might be taking multiple drugs at once, which can also impact how the drug is absorbed and eliminated.

In Phase 1, subjects are also given repeated doses over time to find out the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) as well as to understand human pharmacology. Once this phase is successfully completed, the medicine can move to phase II, which will study the potential benefits of the drug in the target population.

Even people who have heard of the various phases of clinical trials may not be familiar with the role that clinical pharmacology plays, but its role in the drug development process is crucial to making a safe and effective medicine.