9 Things You Didn’t Know About Vaccines

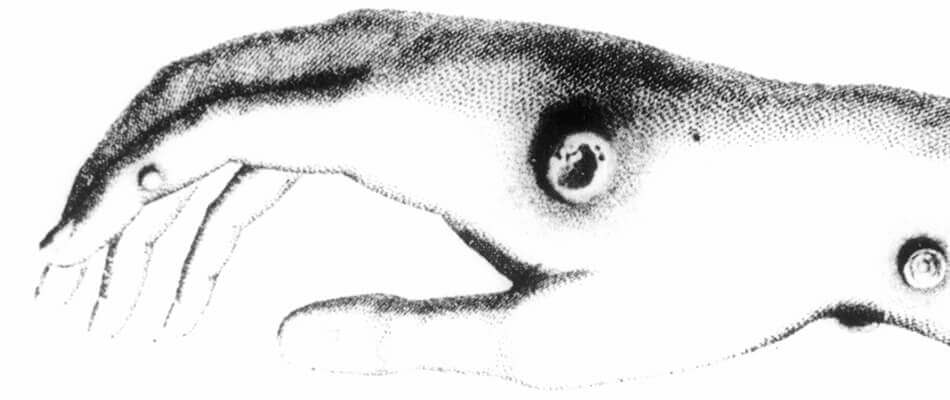

The cowpox pustules on the hand of a milkmaid in the 18th century provided the first vaccine ever created. (Science Photo Library)

Vaccines have a long and storied history, from milkmaids’ cowpox pustules to snorting the scabs of infected people.

The first vaccine was administered in 1796. In the two centuries since, dozens of vaccines have led to the salvation of millions of lives, from George Washington’s troops to children around the world.

Herewith, a primer on vaccines’ most memorable moments.

1. The process we know as vaccination, or purposefully trying to control an infectious disease by applying a vaccine, had its humble beginnings in 1796, when an English physician named Edward Jenner rubbed cowpox pustule liquid — harvested from the hand of a milkmaid named Sarah Nelmes — into some scratches on the arm of eight-year-old James Phipps. Jenner was inspired by the fact that local milkmaids never got smallpox, but were perennially getting cowpox.

Ultimately, his theory that inoculating against the far more deadly strain of smallpox could be achieved by direct exposure to its more benign cousin cowpox proved itself in practice. Phipps never contracted smallpox, which at the time killed 400,000 people every year, and on successive inoculations didn’t develop cowpox either. Jenner’s idea took hold, and gradually grew in scope and reach. By 1980 the once-population-decimating disease was declared globally eradicated.

Louis Pasteur, inventor of the germ theory of disease, in his laboratory. (Science Photo Library)

2. Prior to 1877, germs weren’t a known entity. That is, until Louis Pasteur proposed the Germ Theory of Disease, which stated that disease was caused by the spread and proliferation of micro-organisms too small to be seen by the human eye. In 1881, Pasteur staged a public demonstration in which he inoculated 24 sheep, one goat and six cows against a particularly nasty germ called anthrax, and left another group of farm animals to go without. Weeks later, he exposed the entire lot to anthrax bacteria. When the crowd re-gathered a few days later, all the un-inoculated animals had died. The inoculated group was left unscathed. Within the next five years, Pasteur had created a vaccine for rabies, too.

3. Hippocrates described diphtheria – a disease of the mucous membranes that hinders breathing and swallowing – in 400 BC, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that an antitoxin, a precursor to vaccines, was developed against the potentially fatal infection. Emil von Behring won the first Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1901 for the feat.

4. In 1952, a polio epidemic in the U.S. included more than 57,000 cases just seven years after arguably the disease’s most famous victim, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, passed away. Three years later, Dr. Jonas Salk pioneered a vaccine using dead forms of the virus. Simultaneously, Dr. Albert Sabin developed a vaccine using a live, attenuated — or weakened — virus. Combining these vaccine approaches to great effect, by 1994, the entire western hemisphere was declared polio-free by the World Health Organization.

5. In 1963, Pfizer introduced a measles vaccine to combat the highly infectious childhood disease. Three years later, the CDC announced a campaign to eradicate measles altogether. Within two years, incidence rates had dropped by more than 90 percent.

General George Washington crosses the Delaware with this troops, who he insisted get vaccinated. (Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art)

6. After failing to take Quebec from the British due to a smallpox outbreak among his soldiers, then-General George Washington insisted on inoculations called variolations (precursors to vaccines) for all his troops in 1777.

7. Considered the unsung hero of vaccines, Dr. Maurice Hilleman developed a vaccine for mumps in 1967, measles in 1968 and rubella in 1969. He combined them into one vaccine, called MMR, in 1971. This one vaccine is credited with saving millions of lives around the world. Hilleman created a total of 40 vaccines over his lifetime.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, credited with bringing the idea of inoculation to the West from Turkey. (NYPL/Science Source/Science Photo Library)

8. The first inoculations in the Western world resulted from the efforts of British expatriot Lady Mary Montagu whose husband was a diplomat in Turkey. In 1715, Lady Montagu had been disfigured by a bout of smallpox, so she had her two-year-old daughter publicly inoculated against the disease in England in 1721 after witnessing the Turkish locals’ practice. “The smallpox, so fatal, and so general amongst us, is [in Turkey] entirely harmless by the invention of [inoculation],” Montagu had written to a friend. “There is a set of old women who make it their business to perform the operation every autumn…”

9. In the 10th century in China, protection against smallpox was achieved by gathering the sore scabs of infected individuals, grounding them into dust, and inserting them into the noses of healthy individuals.

—Johnna Rizzo